Ministers

Could Realise Their Ambition for Car-free Lifestyles in Eco-Towns

But Only if the Current Shortlist of Sites is Abandoned

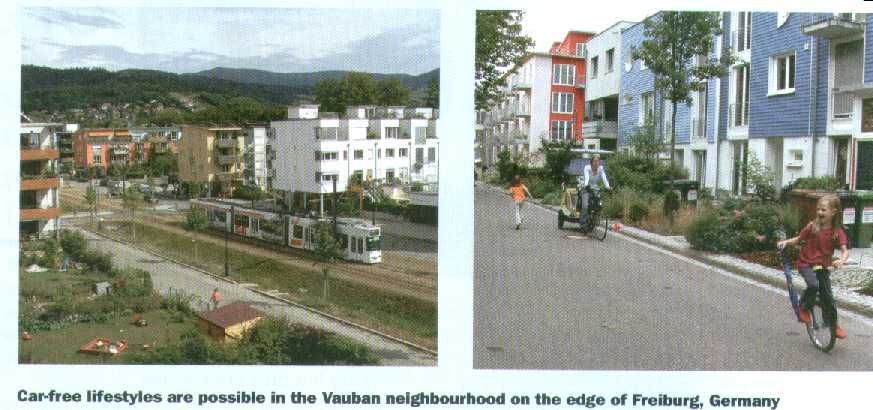

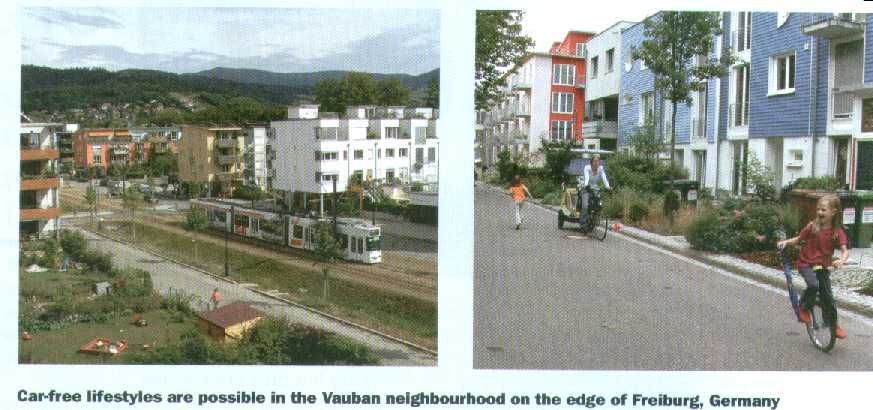

Eco-towns “will follow the most ambitious European models, where only half of households rely on a car”, according to Housing Minister Caroline Flint. Although the word ‘rely’ is ambiguous, writing in The Guardian, Flint related this statement to Vauban the carfree neighbourhood on the edge of Freiburg, where most households do not own a car.

Carfree areas and carfree living are central to the transport guidance for the eco-towns, for very good reasons. Although the relationship is not a simple one, car ownership exerts a powerful influence on car use. Or to put it another way, if 95% of households in a new settlement like Cambourne or 94% in an urban extension like Poundbury decide, for whatever reason, to own a car, we should not be surprised when all the other policies designed to reduce car use spectacularly fail. 81% of Cambourne’s working population and 75% of Poundbury’s drive to work, according to two recent studies. The 2001 average for England was 55%, for Vauban: 14%.

So is this pattern inevitable, or are there circumstances, even in Britain, where people may make very different choices? This has been a key question for my research. One adult in six currently lives without a car. Cost is the key factor for between a third and a half of these people. Some are unable to drive, but a substantial proportion lives without a car by choice (‘carfree choosers’). One of my 3 samples included members of environmental organisations. Leaving aside environmental reasons, the most common response to the question: ‘why do you live without a car?’ is: ‘I don’t need one.’

Amongst the driving population, some say they would like to give up their car under certain circumstances. Many of us say things we don’t mean, but some of these people have actually done this in the past. Probing their reasons can bring insights into the circumstances which encourage people to acquire cars, or enable them to live without one.

Carfree choosers tend to be younger and more affluent than other non-car owners. The vast majority live in larger towns and cities. Most of them are positive about urban living, although some would like to move to smaller places, or closer to countryside – a desire which is often constrained by transport considerations. Those of working age generally prefer to live within walking or cycling distance of their work, or failing this on a convenient public transport route. Most of them live near centres with shops and other facilities.

Whatever their patterns of local travel (many of them prefer to cycle) access to rail for longer distance travel was important to nearly everyone I interviewed who was living without a car. For some, this means living within walking distance of a station. For others living in larger urban areas, multi-directional bus or tram services may be enough – although even in these cases, the town or city centre railway station is never very far away. Carfree choosers of working age are rare in smaller towns; the few that I did interview seemed particularly dependent on good rail links.

Small towns linked to but separated from larger conurbations tend to suffer from car dependency. This is true, not only in this country, but also in city regions like Metropolitan Stockholm. Good rail links have helped to reduce the proportion of journeys made by car from the central areas of satellite towns, but the advantage is undermined by increased journey distances.

This was clearly a danger with the original concept of eco-towns, but not necessarily an insurmountable one. During the work on the transport guidance, Carfree UK, Sustrans and the Campaign for Better Transport wrote to the Government departments pointing out the problem and suggesting that eco-towns should be either:

To enable people to live without cars, the integrated towns must be able connect with the public transport networks of existing conurbations, without relying on separate in-and-out services. Although walking, cycling and buses are likely to account for more journeys, access to rail is critical, because without it, high levels of car ownership will undermine the rest of the strategy as in Cambourne and Poundbury. A station in the town centre would be an advantage for the integrated towns, and essential for any larger eco-towns designed to achieve greater self-sufficiency.

We received no response to our paper, and the shortlist confirmed our worst fears. In two cases a specific location has not been identified. Of the other 13 only one, Pennbury near Leicester, could conceivably fulfil the ‘integrated town’ criteria. In the other 12, the ‘parent’ conurbations were either too distant, too small or both. None of them seems designed or located to grow towards self-sufficiency. Railway lines are distant from some of the sites and peripheral to others. The physical shape of most of the proposals owes more to land ownership and politics than any serious attempt at sustainable design. The worst example is the developers’ proposal for Marston. For the euphemism ‘linked settlements’ read: disconnected sprawl.

The shortlisted areas are shown as green blobs in the consultation paper, Ecotowns a Greener Future (on communities.gov.uk). The more specific developers’ proposals which led to them are illustrated on cpre.org.uk. Take a look at a few of them and ask yourself: would you be happy living there without a car?

The selection process has failed to produce a shortlist of sustainable locations because it has turned the planning system, the ‘wrong way round’, starting with proposals based on existing landholdings. A programme like this has never run before, so why would existing landholdings reflect the most sustainable locations to build eco-towns?

The consultation paper talks of a sustainability appraisal considering other locations not on the shortlist, which provides a glimmer of hope that the programme can still be rescued from failure in its own terms, providing CLG is willing to disappoint the expectations it has raised amongst promoters of unsustainable sites.

If the Government cannot trust regional and local planning bodies to do the job, it must conduct an objective national search, as was done for the post-war New Towns, but with sustainability as its overriding objective. Land ownership must play no part in the selection criteria; if necessary, public sector land assembly mechanisms may need to be used. Integrated towns well served by rail should be the first objective. If sufficient sites cannot be found for these, then one larger eco-town designed to grow towards self-sufficiency would cause less damage – environmental and political – than carbon-hungry car-dependent satellite towns chosen from this ill-considered shortlist.

Steve Melia is a Founder Member of Carfree UK, a freelance journalist and PhD student at the University of the West of England